Written evidence to the national medical training review in 2025

Wen Wang, Jennifer Creese, Kevin Harris

03 October 2025

In view of resident doctors’ exodus crisis and challenges to ensure training quality, the NHS England launched the national medical training review in April 2025, our evidence was accepted.

Q6: To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement? To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement ‘The current model of postgraduate medical training meets the personal and training needs of most doctors?

Our studies (outlined below) suggest that the current model of postgraduate medical training often fails to meet the personal and many instances the training needs of a significant share of doctors out of almost 1500 in our study. In particular urgent reforms are needed to prevent resident doctors from burnout and a worsening of the current exodus crisis.

As the British Medical Association (BMA) 2022 survey reported 40% of resident doctors stated an intention to leave the NHS within five years, and this is particularly acute among Foundation Year (FY) doctors. Only 25% FY doctors carried on training after completing Foundation Year 2 in 2023, a sharp drop from 71% in 2011 (the General Medical Council, 2023).

Our research with almost 1500 resident doctors and 90 trainers across more than 30 NHS Trusts has found that

- Only 50% resident doctors and 44% trainers agree or strongly agree that current model of training provision are adequate at their local Trust.

- Only 20% resident doctors and 36% trainers perceive adequate support from NHS Trust senior leaders (CEO, Medical Director, Director of Medical/Clinical Education, Senior nurse, HR etc.).

- Foundation Year (FY) doctors have a poorer perception of training than other trainees (Core Trainees or Speciality Trainees)

- Fair workload is the key to meet training and personal needs of resident doctors, but the gap between intended and implemented medical training at local NHS Trust persists

Our recommendation is that further reform is needed to ensure proper implementation of postgraduate medical training and we propose the following framework (PRIM) as follows:

In addition, trainers and medical education leaders at NHS Trusts suggest the new curriculum should address the following:

- Expectation Management: Enhance final-year MBBS and Trust induction programs to better align new doctors’ expectations with the realities of NHS, mitigating early disillusionment.

- Representation: Ensure dedicated representation of Foundation doctor (FY1/FY2) on medical education committee to advocate for their specific needs.

- Protected Development Time: Guarantee protected time within FY training for CPD, research, teaching, and quality improvement;

- Workload Analysis: systematically review FY doctors’ workloads to identify and reduce low-value-added tasks (e.g., repetitive administrative duties) that hinder clinical learning.

- Social science Curriculum: Incorporate training in emotional intelligence, human factors, and leadership to equip them with skills and knowledge to address systemic challenges like microaggressions.

Studies in the UK and internationally have identified heavy workload as a critical factor driving resident doctors’ attrition (Byrne et al., 2021; Jagsi & Surender, 2004; Lock & Carrier, 2022; Wallace and Lemaire, 2007; Zeng et al., 2024). However, it may not be workload in and of itself, but rather whether work activities are seen as learning-related which is the important factor. For example, UK and European resident doctors have a legally capped average working week of 48 hours, whereas those in non-EU countries like Australia, the USA, and Canada can often work average 60-80 hours per week (Breuer et al., 2024). Ironically, these countries are among the top destination countries for UK resident doctors emigrating for work (General Medical Council, 2022).

The General Medical Council (GMC) and NHS England’s National Education and Training Survey (NETS) consistently highlight a prioritization of service provision over learning in resident doctors’ training. This focus on short-term targets (service-related workload) over medium-term benefits (training needs) is seen as unfair workload by resident doctors, leading to poor training evaluations, burnout, and dropout intentions

Using a mixed-methods design, our study demonstrates that a fair workload and a balanced approach to training and service provision are essential to meeting resident doctors’ personal and professional needs, thereby reducing burnout and attrition. Achieving this requires committed support from NHS Trust senior leadership which lacks in the current training model.

Methodology

Our evidence derives from a completed project, ethically approved by the Health Research Authority [0904UE]. The dataset includes 1,455 resident doctor survey responses, 35 doctor interviews, 90 trainer survey responses, 5 trainer interviews across 32 NHS Trusts, and insights from 10 knowledge-exchange meetings with 35 senior leaders across 10 NHS Trusts. For more details please see: careinuncertainty.le.ac.uk

Research methods

Quantitative analysis (STATA 17) identifying determinants of resident doctors’ wellbeing and training needs (n=1,318: 656 FY1-2, 662 senior doctors (CT, ST) by excluding 229 ‘F3’ doctors.)

Reflexive Thematic Analysis of interviews with 35 residents and 5 trainers on training/work experiences.

Trainer evaluations of training provision (n=90).

Group comparisons to assess the perceived needs fulfilment between FY doctors and other trainees (Table 1).

Senior leader feedback (35 senior leaders from 10 NHS Trusts) through knowledge exchange activities.

Statistical notation: *** = 99% significance (positive/negative coefficients indicate directional effects).

Findings (some highlights)

Quantitative methods Descriptive analysis

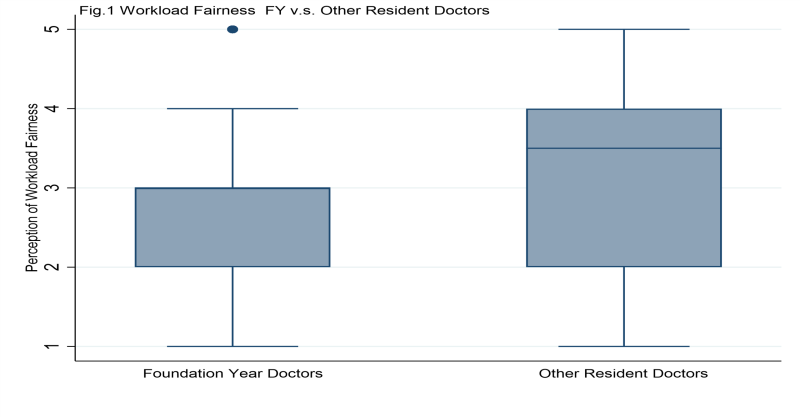

In Fig 1, it shows that FY doctors have a significant lower evaluation on the fairness of their workload compared with senior trainees, with 52% v.s. 70% agree or strongly agree their workload is fair (the difference is statistically significant, |T|=6.03 in Table 1).

Perceived poor training provisions by trainees and trainers

The poor perception of training provision is evident among trainees and trainers. Only 23 % of FY doctors felt that they have adequate training provision; this is about 50% among senior trainees and 44% among trainers. In addition, less than 50% of trainers (90) felt positive about the training facilities, support and resources provided at their Trusts.

Perceived poor support from NHS Trust senior leaders by trainees and trainers

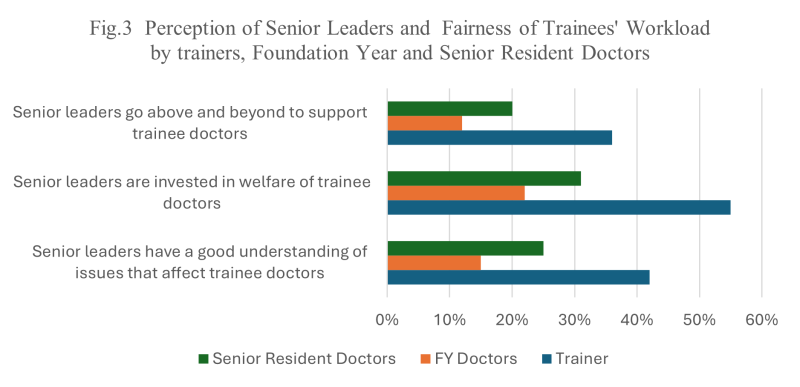

Both resident doctors and trainers report very poor support by NHS Trust senior leaders (e.g., CEOs, MDs, DMEs, senior nurses) towards resident doctors. This is captured by perception of poor understanding of—concern for- support—trainees. As Fig. 3 shows, only 15% of FYs agree or strongly agree that senior leaders understand their issues, compared to 25% of senior trainees and 42% of trainers.

The recommendations submitted in this call for evidence are based on a comprehensive scientific analysis currently under review for publication in a high-impact journal; therefore, we are unable to disclose substantial findings at this stage.

Conclusion

Medical training in the UK healthcare system represents a ‘wicked problem,’ characterized by escalating demands and competing priorities between education and service delivery workload. In addition, reforms of training will inevitably affect other sectors of the NHS workforce. However, a coordinated, collaborative approach—prioritizing training, incentivizing effective education, and aligning with modern clinical needs—can cultivate a skilled and resilient workforce capable of delivering world-class patient care.

Acknowledgement

Our NHS Collaborators who co-created the on-going medical education interventions with us and reviewed the submission include

Dr Hany EL-Sayeh, Consultant Psychiatrist, Director of Medical Education, Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust

Professor Helen Steed, Consultant Gastroenterologist, Director of Medical Education at Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, Lead DME in the West Midlands; Mr Mark McCarthy, Consultant Vascular Surgeon, Chair of the East Midlands DME group, Director of Clinical Education/ Associate Medical Director, University Hospitals of Leicester. We also thank Professor Roger Seifert for his insightful comments.

References

Breuer, R. M., Waitzberg, R., Breuer, A., Cram, P., Bryndova, L., Williams, G. A., … & Rose, A. J. (2023). Work like a Doc: A comparison of regulations on residents’ working hours in 14 high-income countries. Health policy, 130, 104753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2023.104753

Byrne, J. P., Creese, J., Matthews, A., McDermott, A. M., Costello, R. W., & Humphries, N. (2021). ‘… the way it was staffed during COVID is the way it should be staffed in real life…’: a qualitative study of the impact of COVID-19 on the working conditions of junior hospital doctors. BMJ open, 11(8), e050358. https://doi.org/10.1016/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050358

General Medical Council (2022). The state of medical education and practice in the UK: The workforce report, 2022. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/workforce-report-2022—full-report_pdf-94540077.pdf

Jagsi, R., & Surender, R. (2004). Regulation of junior doctors’ work hours: an analysis of British and American doctors’ experiences and attitudes. Social Science & Medicine, 58(11), 2181-2191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.016

Lock, F. K., & Carrieri, D. (2022). Factors affecting the UK junior doctor workforce retention crisis: an integrative review. BMJ open, 12(3), e059397. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059397

Wallace, J. E., & Lemaire, J. (2007). On physician well being—you’ll get by with a little help from your friends. Social science & medicine, 64(12), 2565-2577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.016

Zeng, Z., Lu, Z., Zeng, X., Gan, Y., Jiang, J., Chen, Y., & Huang, L. (2024). Professional identity and its associated psychosocial factors among physicians from standardized residency training programs in China: a national cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Medicine, 11, 1413126. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1413126